Here at True Investigator, we have journeyed to the highest peaks, the deepest oceans, and the darkest rainforests. And yet, in all the biomes we have visited, there is one that we have always sort of…overlooked. The thing is, this unexplored environment isn’t in deep space or some unexplored cave, but right above our heads. We are speaking, of course, of the very sky itself.

In the sky, the only constant companion that a creature has, is the wind itself. We understand how birds developed flight, and we know why so many evolved to live a life on the wing, but it is rare to find an animal that spends its entire existence in the air—rare, but not impossible. Believe it or not, there are birds that sleep while in flight and insects that can travel the length of entire continents on tiny, paper-thin wings.

In this article, we will examine those alighted creatures and many more. We will explore the lives of those remarkable few that have—for one reason or another—chosen to live a fully airborne lifestyle. So prepare for to journey with us to a place that we humans have only recently begun to explore ourselves. On this adventure, the sky’s the limit!

The Common Swift

The following list will have a number of fascinating entries that one could describe as “sky dwellers,” but few animals deserve that title more than the common swift, a little bird with remarkable aerial skills. Once this tiny bird fledges, that is to say, once it is ready to leave the nest, it may not touch land again for many years.

Swifts are one of the few vertebrates in existence that eat, drink, mate, and even sleep while in flight. The latter of these happens because of a technique called unihemispheric slow-wave sleep, which essentially involves the bird shutting down one hemisphere of its brain at a time. Through this adaptation, the swift can can rest in mid-air without falling to its doom. In fact, according to the National Audubon Society, certain swifts have been recorded flying continuously for 10 months or more. These studies were performed using tracking devices and indicate that the bird only landed briefly to breed during that 10-month period.

Part of the reason that swifts spend so much time in the air has to do with their morphology. Possessed as they are of scythe-like wings, streamlined bodies, and short legs, they are rather awkward and ungainly on land. Those little legs are almost useless for walking, in fact. That, coupled with their diet of winged insects and exceptional aerial ability, means that living on the wing is the only way they can truly function.

The Albatross

Childhood fans of the Rescuers movies will know that albatrosses are some of the best long-distance flyers around. The aptly-named wandering albatross is particularly savvy at this and currently boasts the largest wingspan of any living bird. Some individual specimens have had wingspans of more than 11 feet from wingtip to wingtip. But size isn’t everything when it comes to long-distance flying, the other attribute one needs is stamina; something the albatross has in spades.

These massive seabirds are practically built for soaring over vast swaths of ocean. They accomplish this using a method of flight called dynamic soaring, which allows them to exploit ocean winds and glide for hours, even days, without flapping their wings. As a result, most albatrosses spend 85%–95% of their life at sea, riding the air currents over the Southern Ocean. They only return to land periodically, alighting on remote islands to breed with others of their kind.

The Frigatebird

Another large and impressive crimson-throated avian is the magnificent frigatebird, an unusual specimen that spends a good deal of its time in and around the Galápagos Islands. Known for staying aloft for weeks at a time, the frigatebird doesn’t rely on oceanic winds to keep it in flight, but thermals and updrafts. This might be because its territory—near the equator—is somewhat more tropical than the albatross. Scientists have observed these birds traveling over 3,000 miles without ever touching down to rest and that included over water.

This is perhaps due to the frigatebird’s inability to swim and the fact that its feathers aren’t at all waterproof. Despite this, frigatebirds feed primarily on fish…just not fish they themselves have caught. That’s right, frigatebirds practice a behavior known as kleptoparasitism, which means they steal fish from other seabirds in mid-air.

The Dragonflies

Dragonflies can trace their origins back to prehistoric times; before the dinosaurs and long before the age of man or even modern birds. This means that these buzzing bugs have been airborne hunters for over 300 million years; though today’s specimens are far less frightening and impressive than the primeval monsters that used to hunt giant amphibians in the primordial swamps.

Regardless of their massive decrease in size, however, today’s remaining dragonfly species are no less impressive to behold. Take the globe skimmer dragonfly for instance. This teensy insect currently holds the world record for the longest known insect migration. It has been known to travel up to 4,400 miles across oceans between India and East Africa. Why does it make this journey you may ask? Well, to breed of course!

In addition to being able to skim across the literal curve of the Earth, dragonflies are among the most agile fliers in the animal kingdom. These dextrous fliers can hover, fly backwards, and even turn 360 degrees in mid-air without batting an eye. This makes them perfect predators, able to snatch other flying insects from out of mid-air within seconds.

The Swallow-tailed Kite

By the tone of the entries thus far, it would seem that predator species are the most well-adapted to life on the wing. The swallow-tailed kite, a speedy raptor that can be found all across the southeastern United States and Central/South America, is a prime example of this. This graceful, fork-tailed predator feeds almost exclusively while flying and can be seen plucking lizards, frogs, and insects from the treetops with ease. It also barely makes a sound as it does this, making it more akin to a diurnal owl than a relative of the falcon.

Kites are also long-distance fliers, migrating across thousands of miles each year between their breeding and wintering grounds. During these long migrations, the raptors spend most of their time in the air, using thermal air currents to travel and help them to expend minimal energy along the way.

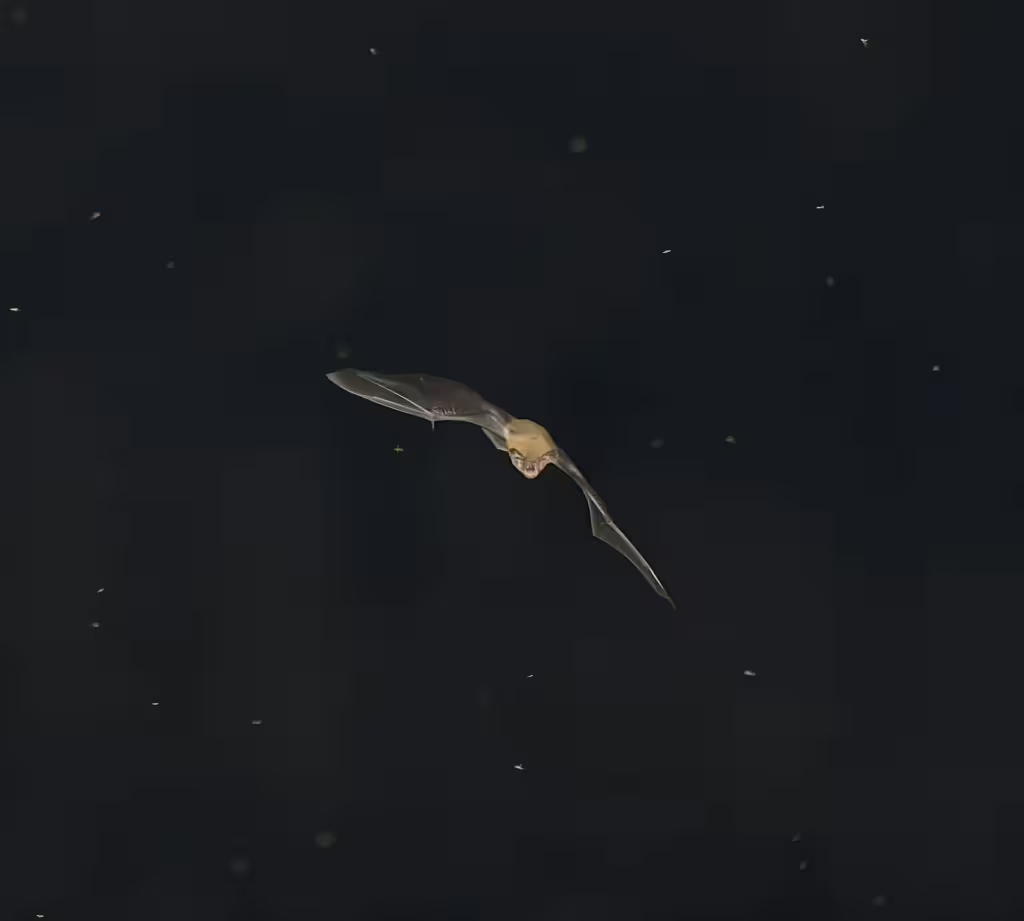

The Mexican Free-Tailed Bat

Many readers will feel skeptical about this entry, but bear with us here for a moment. Bats are the only mammals that are capable of sustained powered flight. The Mexican free-tailed bat, in particular, is able to reach altitudes of over 10,000 feet. It can also flitter about at speeds of more than 100 mph, which is darn impressive for such a teensy little creature. Though they roost in caves like most of their kind, these bats spend nearly all their time awake, flying in constant motion and feeding on insects as they flitter past them, mid-flight. Mexican free-tailed bats are also migratory, flying over 1,000 miles between their habitats in Mexico and the United States every year.

The Hoverfly

The tiniest creature on our list is the hoverfly, a creature that most people don’t even realize is its own species. Often mistaken for bees, hoverflies also feed on nectar, and can be seen hovering near flowers like teeny tiny hummingbirds. They differ from bees in a number of ways, but are no less vital to the pollination of their floral neighbors than the apian creatures they mimic so well. These expert aviators that spend nearly all their lives up in the air and are so-named for their uncanny ability to hover in place. Thanks to their precise visual processing and rapid wingbeats, hoverflies are capable of darting suddenly in all sorts of directions with ease. Some subspecies have even been seen migrating in large numbers across Europe and Asia.

True Investigator Says…

As you can see, the sky is not a place for most animals. In most cases, it is simply something that flying creatures pass through on their way to their next roost. To the species mentioned above, however, the sky is as much a place to breed, feed, migrate, or rest as any nest upon the ground. Terrestrial as we are, these concepts might seem hard to understand, but we humans have only been sojourning up into the skies for the better part of a century or so. In that sense, we are novices, especially when compared to the amazing aerial animals that have claimed the skies since before even the dinosaurs ruled the Earth.

Discover more from TrueInvestigator

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.